What happened to my dark-yolked eggs?

I have seen lots of conversation online about consumers’ local, pasture-based egg source selling them pale eggs in the summertime—even paler than what is found at the supermarket!

Naturally the reaction is, “Why am I paying more and going to greater lengths to get what appears to be an inferior product?”

Good question.

Eggs, like all seasonal foods, change in appearance, quality, and even taste according to environmental factors. Here in east Texas, the animals’ biggest challenges are keeping cool during our long, hot sunny summer days. In fact, our hot, dry summers are almost like northern winters in the sense that the plants and animals go into survival mode and don’t produce as much or as well as they do during the rest of the year.

But back to the question. How do you know that your locally-sourced pasture-raised eggs are better than supermarket or health food store “cage-free,” “organic,” and “free-range?”

Let’s not go too far into what “they” are doing wrong—let’s just talk about what “right things” you should look for when sourcing eggs and the reasons for doing so.

What to look for in an egg source

1. Exposure to sunshine.

Being in the sun allows chickens to naturally produce vitamin D. It also helps their environment to be cleaner because of the sun’s sanitizing ability. Pathogens cannot take hold in a UV-washed environment. Of course, the chickens tend to hunker down in the shade during the hottest part of the day, but they still get plenty of sunshine exposure.

2. Exposure to growing vegetation.

Real vegetation is one of the main sources of the detoxifying agents like chlorophyll and beneficial polyunsaturated oils in pasture-raised eggs, such as CLA and omega-3 fatty acids. Sure, those can be artificially supplemented in conventional chickens’ diets, but doesn’t that defeat the purpose? Perhaps the natural seasonal change from lush spring green to fibrous summer forage plays a role in producing healthy chickens, eggs, and egg-eaters. It is certainly something to consider!

3. Exposure to real bugs.

Eating insects is where chickens get their vitamin K as well as other hard-to-find nutrients. Plus chickens have fun chasing the bugs and chasing each other when somebody finally catches one. Thank goodness for chickens so we don’t have to eat bugs ourselves just to get vitamin K! Eggs are much tastier than grasshoppers.

Pro tip: “Cage-Free,” “Free-Range,” and “Organic” labels DO NOT indicate that the chickens were actually raised outdoors. It can simply mean that they “have access” to outdoors, which can be a tiny enclosed concrete pen with screen walls. No grass. No bugs. No sunshine. Better to look for “Pasture-Raised.” Better still to visit the actual farm!

4. Avoiding Genetically-Modified Feeds (GMOs).

Genetically-modified organisms come in a variety of forms, but the primary ones you’ll see is soy, corn, cottonseed, rapeseed (aka canola), and alfalfa, and the primary use for these kinds of crops is for livestock feed. If your farmer doesn’t know whether the feed contains GMOs, it PROBABLY DOES. It can be extremely difficult to source non-GMO feed at typical farm supply stores, as livestock feed is one of the top outlets for GMO products.

GMOs haven’t been required to be tested for safety AT ALL, and the few trial feeding experiments that have been done indicate that feeding animals GMOs results in stomach and intestinal problems and development of tumors. Thanks but no thanks.

5. Avoiding soy.

Soy contains lots of nasties, including estrogenic compounds, high levels of phytic acids, and goitrogenic phytochemicals. Soy is cheap and high in protein. Soy also happens to be a plant and so has become extremely popular among chicken feed producers because the necessary protein levels for healthy hens can be attained while still using a “vegetarian-based” feed. Newsflash: chickens aren’t vegetarians. They need bugs! But when you put 80,000 of them under one roof, there aren’t enough bugs to go around. Thus the “need” for high-protein soy.

Chickens do need some supplemental protein, but there are better alternatives that are lower in those bad phytochemicals and are not genetically modified (yet), like field peas, sesame, peanuts, milk, meat, and bugs! There are those bugs again…

6. Avoiding antibiotics.

There are three ways antibiotics might be used in a laying chicken’s life. First it is when the birds are young and it takes the form of “medicated” feed.

The second is similar, when adult chickens are fed “medicated” feed to prevent disease and reduce stress. The problem with long-term use of low-level antibiotics is that evidence suggests this is where your superbug pathogens come from. Bacteria always exist in food and among animals, and when exposed to non-therapeutic antibiotics, they grow resistant and become extremely dangerous. Antibiotic use like this necessitates bigger and badder guns to provide food safety such as chlorine or ammonia washing, pasteurization, and irradiation.

The third use is the occasional, therapeutic use of antibiotics for emergencies. When a chicken is sick and the antibiotics would save her life, ok. At Shady Grove Ranch, we prefer simply to “do the chicken in,” but we rarely have sick birds to begin with.

7. Avoiding arsenic and other growth stimulants.

Arsenic is (surprisingly) widely used among poultry growers to help the birds to grow and remain productive in a stressful environment. It acts as a appetite stimulant and helps the birds to ward off certain confinement-related diseases. In meat chickens, it produces a nice “healthy-looking” pinkish flesh in the chicken. But it’s a poison and we feel it really has no place in food production if there is a better way to produce the food, such as using strategies that allow the animal to naturally detoxify and live in an environment that is appropriate and therefore very low stress.

Pro tip: “All-Natural” labels are basically meaningless and don’t refer to the way the animal was raised. So if your eggs claim to be “all natural,” they may still have come from chickens that were fed antibiotics, GMOs, and arsenic. Yuck!

8. Rotational Management.

Rotational Management is key to good chicken health, good soil health, tasty eggs, and sustainable production. When any animal is left too long living in its manure, it will get sick. Just like humans. Animals should be rotated across pasture so their manure has time to be digested by the soil and rendered safe and useful to the land. In other words, chickens shouldn’t have to live in their own toilet. This should be common sense, but we’ll be the first to tell you that it takes a lot of work and ingenuity to actually put it into practice. Many backyard chicken operations employ the use of permanent pens that ultimately lead to the chickens having health problems. Thankfully the use of “chicken tractors,” or small mobile pens, is on the rise! Why is rotation so hard? Because everything LOVES to eat chicken and lots of protection and planning are required to keep predation under control while still allowing the chickens to forage freely. Chicken tractors are a nice small-scale solution to both problems.

What about “confinement?”

Notice “avoid confinement” isn’t on this list. What does “non-confined” mean, anyway? Whether it’s a tiny cage or a perimeter fence around 100 acres, the chickens have to be confined somehow. This term takes a bit of common sense to interpret, just as with “cage-free,” or “free-range.”

Chickens don’t really need a huge amount of space if they are managed well. If you find a local farmer who keeps his chickens in a small pen, but who is dedicated to moving them frequently, that’s fine! Even farmers that lock their chickens in at night but allow them forage time during the day are doing great. After all, a farmer has to protect his flock from predators and there are lots of ways to do that while still allowing for a healthful, sustainable way to raise them.

The main thing to look for is not whether the chickens live “in a cage,” but rather, whether that cage contains these elements that are important for the birds’ health. Of course at some point even a regularly rotated cage can be so small that it causes the birds undue stress, which will be obvious by the emergence of missing feathers and bodily injury. All the more reason to go SEE where your food comes from!

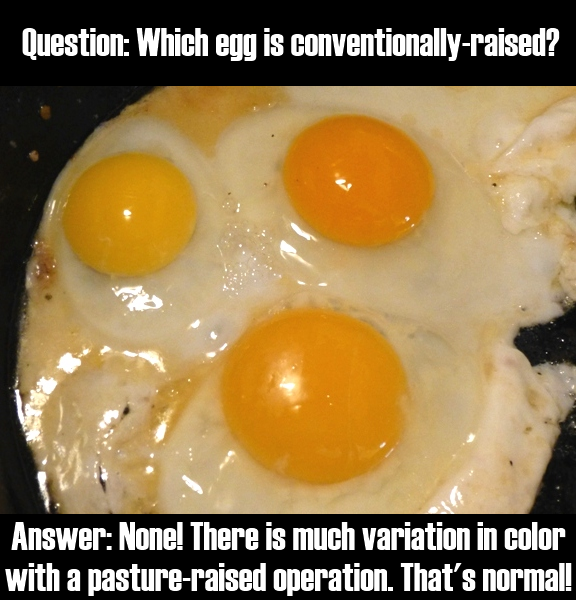

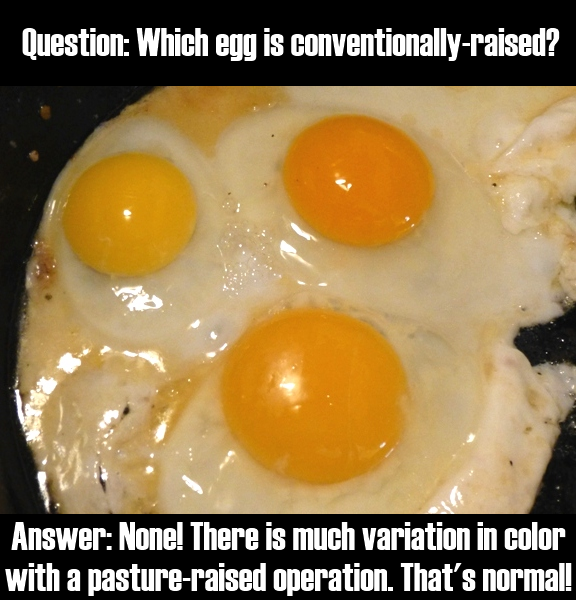

Does it matter what color the yolks are?

We started this conversation talking about yolk color. There are diverse opinions about what the color of the yolk means regarding nutritional value. But there are plenty of ways to boost the color of an egg yolk, whether naturally or unnaturally. For example, it is known that if a chicken is fed mostly yellow corn, the yolk will be fairly dark. That same chicken on a white-corn diet will have much paler yolks. And chickens who have never even seen real grass may be fed ground marigold petals which lend a beautiful golden hue to the yolk. Maybe the color isn’t as important as some make it out to be…

All we know is that we raise our chickens as healthfully as possible, and here is what happens seasonally with their eggs:

The Seasonality of Eggs

Spring: Eggs are small, whites are dense and very jelly-like, shells are very hard, and yolks are dark, sometimes almost so orange they are red.

Summer: Eggs are larger, whites become more watery, shells get thin, sometimes too thin, and yolks are large and pale and break easily.

Fall: After the rains start, the eggs return to spring-like characteristics.

Winter: When it gets cold enough that the grass stops growing, the eggs return to summer-like characteristics.

This article is already really long, but if you care to consider why this happens, here is our hypothesis:

Spring/Fall

When the grass is growing rapidly and very lush, it is easy for the chickens to eat. The phytochemicals in the grass lend an orange tone to the yolk and the chickens eat much more forage than feed, yielding a smaller, tastier egg. The grass is in its protein stage, so the hen can produce better quality proteins for a denser, more jelly-like egg white. The combination of cool weather (i.e. low stress on the hen’s body) and high mineral content of the grass allows the hen to utilize all the calcium she is eating and make a strong shell. Yes, the yolk is darker and very likely has a different nutritional profile than a summer egg, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the egg is more nutritious. It is just different.

Summer/Winter

When the grasses mature (i.e. go to seed) in hot or very cold weather, the available forage is considerably lower in protein and more difficult to eat and the hen must rely more on her feed ration than on the grasses. In summer, she drinks lots of water to keep cool and the egg white ends up more watery in texture and less dense. The heat makes her body less apt to utilize calcium and her shells get thinner. When it rains, there is a noticeable difference in the shell and yolk quality, but it only lasts for a day or so. Yes, the yolks are lighter in color than spring eggs, and maybe even lighter than store-bought eggs (where the chickens are likely fed a highly controlled diet so the yolk is the same color all year long).

Perhaps it is good to embrace the seasonal changes in our food. Don’t be afraid to ask questions about changes in quality of your farm-raised foods. But don’t be afraid to eat with the seasons, either!