Before I tell you what really happened to the turkeys that fell victim to a predator attack a few weeks ago, I wanted to share a bit of farm turkey history for your entertainment and education. Our very first batch of turkeys was actually a bit accidental. Sure, we planned to get into turkeys eventually, but that first year we landed in Jefferson, we were focused on getting the cattle operation up to speed, building fences, shelters, freezers, and all the absolutely-necessaries in the first year of a pasture-farm.

But we happen to have a friend who is into all-things-natural-and-

The next year we raised them from day-old poults, but only a small batch. The next year after that we raised more, and each year following, we kept tweaking the process: the hatchery and the breed and the timing and the feed and the brooder and the water supply and the pasture shelters and the harvest dates and the processing help and the pickup schedule and the reservation strategy and the freezer storage and the size distribution and all the little details that go into producing these special, seasonal, pasture-raised meats.

Some of you may remember the year all the turkeys turned out about 8 pounds smaller than expected! And another year the smallest bird we had was over 16 pounds! And the other year where we harvested them right at the last minute so that we actually had to make a special turkey delivery run just to accommodate the altered harvest schedule. Yet another very hot and dry year, the turkeys started randomly killing each other, and continued until we determined that they needed extra free-choice salt to go with all the water they were drinking! The mineral salt stopped the mayhem in its tracks. Makes you wonder what some good mineral salts would do for our society…

Oh, turkeys. It’s all so complicated! To be honest, last year was so tough with so many random mortalities, that we almost threw in the towel. But our chicken season this spring was so full of wonderful breakthroughs in learning how to do Pastured Poultry that we decided to give it another good go.

This year, 2017, we have produced the most turkeys ever, and they are way happier and healthier than ever because of all the careful changes we’ve made in our pasture-management. Turkeys are very likely the most difficult livestock to raise because when they’re young, they are very fragile, and when they get older, they just get themselves into So. Much. Trouble.

But this year was going well. Maybe we had finally made peace with these wild-ish birds. Many of our customers have told us they’d buy turkey year-round just to diversify their grocery portfolio, and because they love it so much. We’re all about pleasing our customers when possible, so it had begun to look tempting. The turkeys this year were doing so well and so much fun to watch. We even discovered that they eat Stinging Nettle, one of the nastiest plants we have at the farm during the summer season. Nothing else eats it. Way to go, Turkeys!

But one tragic morning just a few weeks ago, we discovered something terrible. Something had killed and partially eaten at least a half dozen turkeys. We found 7 carcasses. Mostly wasted and scattered across the pasture. A terrible loss, and less than a month away from harvest. Some of those birds were probably already at harvest weight.

We immediately moved our best guardian dog, Zeke, in with the turkeys. He’s trustworthy and attentive and has easily solved all of our predation problems with only his intimidating presence. I’m not sure he’s ever actually had to attack anything. He had been in with the young laying hens to protect our hefty investment in raising 470 hens right up to laying age. We had just obtained another Pyrenees female, but she was still in training with Zeke. She’d have to get on-the-job training now because Zeke was needed elsewhere.

We penned up the other farm dogs and set out baited snares near the turkey paddock. Matt camped out after dark with the rifle and spotlight in hopes of catching whatever-it-was, but nothing came, and it was too dark, anyway, to make that work. Finally, at a reluctant bedtime, I turned off the bedroom fan so we could hear, and Matt and I slept fitfully that second night, waking at every tiny noise in the dark and wondering if it was a turkey attack.

The next morning I waited for the report. Not good. Two more turkeys lost. Traps untouched. Pyrenees still on guard. What happened? When did it happen? And what kind of an animal would challenge the 100+ pound alpha Pyrenees? Was Zeke becoming ineffective? Or perhaps we were dealing with a pretty serious predator…

On the third night, Matt decided to go out early and watch.

That was the key.

At dusk, when the turkeys were supposed to be heading in to the roost, for some reason were fluttering around and being crazy instead. (Much like my own children at that hour some days!) And because of their large size, a gang of them could easily (and did) push some stragglers toward and OVER the portable electric fence! It’s a fairly flimsy fence, made lightweight enough to be picked up and carried to the next paddock. Mobile-pastured. What we’re all about.

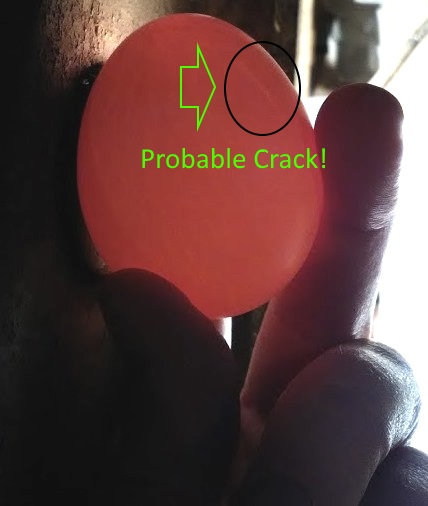

But the flimsy fence, electric or otherwise, couldn’t stop a sea of 20+ pound turkeys from bowling over it in their evening excitement. Who knows what was going on in their bald, bird-brain-size heads? But the end result was a few turkeys trapped on the outside of the fence, with no feathered ocean of bodies to push them back IN. No guardian. No shelter. Totally defenseless against attack.

It wasn’t Zeke’s fault. It really wasn’t even the predators’ fault. It was the turkeys’ fault! Some coyote had simply stumbled upon a few lost and vulnerable turkeys some evening and helped himself. And he just so happened to find seconds the next night. But by the third night, we got smarter and were able to move the exiled turkeys back into the fence, up onto the roosts where they were safe and cozy. And so, every night since then, we added the daily chore of “Tucking In The Turkeys.”

And that, friend, is why we do not raise turkeys year-round.

They’re wonderful creatures, but a poor farmer can only take so much of a good thing. They head to Freezer Camp next week. But you can meet the crazy things in person TOMORROW during our Farm Tour. It’s not too late to sign up here (https://shadygroveranch.net/

Oh, and if you haven’t yet signed up for a turkey, we have just a few spots left (http://shop.shadygroveranch.