Bird’s Eye View of The Life of a Chicken

Among the misunderstandings that abound concerning industrialized products, probably food production has some of the most. Marketing committees have developed clever ways of giving facts and presenting half-truths so that the pleasant pastoral images evoked when a shopper sees “Farmer Joe’s Free-Range Eggs” on a label that he or she feels comforted to know that the hens that gave those eggs was roaming merrily about a meadow in Farmer Joe’s backyard. Consumers are instinctively concerned about where their food comes from. If they thought it came from the farm equivalent of a torture chamber, they might not buy.

This article will give you a brief glimpse into the different “species” of production chickens from the perspective of the chicken. This is a fiction, of course, but there are lots of facts about food production within. Keep in mind that chickens that produce eggs are entirely different in breed, feed ration, rearing technique, and productive age, from chickens produced for meat. Most folks don’t know this and assume that the juicy, fried chicken they are eating was once a laying hen, if they think about it at all.

You will meet 6 chickens:

- Grim Gertrude, the commercial laying hen;

- Tricky Tina, the Free-Range or Cage-Free commercial laying hen;

- Mediocre Molly, the fixed yard hen;

- Lucky Lucy, the pasture-raised laying hen;

- Juiced-Up Jerry, the commercial meat chicken;

- Frisky Freeman, the pasture-raised meat bird.

Here are their stories.

Grim Gertrude, The Commercial Laying Hen

My name is Gertrude, and I’ve never seen the sun. I live in a big house with 80,000 of my sisters. I live in a cell with a few other gals, but I can’t move around much, so I don’t know how many of us are in here. Besides, it’s dark most of the time, so we just sit around eating and laying eggs every 30 hours or so. When I get bored, I pick off my neighbor’s feathers, or maybe some of my own. I can’t really stand up or stretch my wings, so there’s not much else to do.

When I was a chick, they cut off my beak so I wouldn’t hurt my neighbors. It’s not that I want to hurt them, but being so close and unable to move all the time can make you feel a little crazy. Not having a beak makes it hard to eat, but since all I eat is mash, it’s not too bad. We have access to it all day long, and there is something in the food that makes me crave more.

I never get to sit on my eggs. As soon as they’re hatched, they roll away to a big conveyor. For the first 3 or 4 weeks after I started laying, the eggs were probably sold as powdered egg product because they are small and irregular-shaped. Now that I’m middle-aged, my eggs, as long as they meet size, color, and density criteria, are sold to folks who crack them and cook them. But if I ever have a misfire, like a double-yolk or a soft-shell egg, those are never sold directly to customers. Customers don’t get to see all the variety I can produce.

I’ve never seen a rooster before, but I’ve heard that they make a hen feel secure. We don’t need roosters to make eggs, so the manager doesn’t bother to keep any. It would be a waste of feed, after all. When I was a chick, I was hatched in a big, warm box. For every future (female) laying hen that was hatched, there was a cockerel (young male chicken), too. There is not much use for roosters of a laying variety, though, so they immediately were sent off to the dog food company.

It smells pretty bad in my house, but I don’t have to live in it too long. My lifespan is 5 years or more, but my useful productive life is only about 2, so my sisters and I will probably end up in some canned chicken soup when the time comes. I wouldn’t make it as a meat chicken—my connective tissue is more developed and would require slow-gentle cooking, and my meat is more stringy because I am older. So into the soup can or pet food cookery I go. There is no waste in commercial food production, you know.

Tricky Tina, The Free-Range or Cage-Free Commercial Laying Hen

I’m Tina, and I lay eggs in exchange for food and shelter. I live in a big giant house with 80,000 of my sisters. From what I’ve heard, I have it pretty good, because I have a nest to lay in (though it is shared), and I get to walk over to it. My house is really smelly—I guess you can’t expect the manager to clean it out with all us hens in the way—but I won’t complain because I have heard it could be worse. I think there’s even a door to the outside on our house, but I’ve never been able to find it. Our food and water is in here, though, so I guess I don’t need to go out there. Some of the girls have said it’s just another litter yard with a roof and walls. Doesn’t sound very exciting. Besides, with all the other girls in here, it takes a long time to get anywhere, and I tend to get a little lost unless I just stay in my own little area.

Mediocre Molly, The Fixed-Yard Hen

My name is Molly, and I have an owner named Farmer Joe. Morning and evening, he brings food to me and my 30 sisters. We’re usually pretty hungry by the end of the day because we’ve searched our yard high and low for bugs, grass, and seeds. I vaguely recall a time when there actually was grass in here. But we just love eating green stuff so much that we ate it all pretty fast. I can occasionally grab a strand of grass through the holes in our pen if Farmer Joe hasn’t mowed yet. He sometimes gives us the clippings from mowing—we just love it!

We live a pretty decent life, but it is a little stressful not having space to roam. A lot of my feathers are missing because my sisters pick on me while I’m trying to eat. But they’ll grow back, I suppose. We have a nice cozy little nesting house, but over time it gets to be pretty smelly in there until Farmer Joe cleans it out. I think he uses the litter in the garden. He sometimes gives us scraps from that garden, but we mostly eat food from the local feed store. It hurts our gizzards a little, but we seem to tolerate it. The bag says something about corn and soy.

On Sunday nights, Mrs. Joe lets us out for an hour or so in the evening. We love that time! That’s when we get to find juicy bugs and berries and nuts from the big tree in the backyard. But Farmer Joe worries about the neighborhood dogs, so he pens us back up at night. Mrs. Joe would let us out more often, but she says we’d destroy the garden if we had too much time in it. We just can’t help ourselves.

We lay eggs for the Joes and their friends, and they are fertilized by our rooster. I’ve heard Mrs. Joe talk about how much better our lives are than commercial hens, who are trapped in a big building with no space to roam or scratch. That does sound bad, but only scratching once a week is a little nerve-wracking. I wish we could pick up our yard and move it around!

Lucky Lucy, The Pasture-Raised Laying Hen

I’m Lucy, and I live at Shady Grove Ranch. I have about 150 sisters right now, and we share about 10,000 square feet of pasture. That amount fluctuates, but we always have access to grass and sky. We have a big house that moves along on the pasture with us, which is a great comfort to us when we venture to new territory. It’s nice to have a roof to run under when hawks and owls fly by. We also have a big electric net around us that keeps the coyotes and skunks out.

Every day, one of the Cadmans walks down and gives us fresh food, cleans our waterer out, and collects our eggs. They always laugh when we give an unusual egg. We like to keep them on their toes. Each week, they give us a new pasture by leap-frogging the nets to an adjacent area. Every other day they move our nest house. I guess they keep us on our toes, too.

They give us a really nice feed ration that complements our foraging well. Because our diet is forage-based and we are exposed to the elements, our eggs change with the seasons. When we have a lot of tiny green stuff to eat, the yolks turn very dark. When the weather gets really hot or really cold and the grass slows down, we rely more on the ration, and don’t produce quite as many eggs.

If the weather is wet, our eggs get a little muddy when we hop in and out of our nest boxes. When the weather changes suddenly, many of us skip a day laying. In the summers when it’s really hot, we stop laying for a bit and our feathers molt. Once it cools down again, the feathers grow back and we start laying, but our eggs are little like when we were adolescents. That’s ok, though, because the Cadmans don’t seem to mind.

If we get too hot, the Cadmans turn our mister on. During the heat we eat more salt than usual. It keeps us calm and helps our fluids to stay balanced. When the grasses are dry, we also eat more calcium to keep our shells nice and firm. The Cadmans try to monitor our behavior and consumption to provide real-time responses to our needs.

When one of my sisters catches a bug, we play a game where we all chase her around the pen. Sometimes someone else catches her and gets the bug. Sometimes she gets it. We all take turns.

We have a few roosters to take care of us. Since they don’t lay eggs, they can spend less time eating and more time watching the sky for predators.

Juiced-Up Jerry, The Commercial Meat Chicken

I’m Jerry, and I will be slaughtered at 7 weeks of age or less. My friends and I live in a big giant house with probably 80,000 other young birds. I grow so fast that I have trouble walking, so I spend most of the time laying on my own excrement. That wouldn’t be so bad, but the air quality around me is so terrible that I have irritated mucous membranes, and when the humans come into my house to clear out my brothers who have died from the high-stress environment, they have to wear masks.

We get plenty of food, but it never really satisfies. Something in it irritates our throats so we eat more to soothe them. My flesh is rosy pink because of the chemicals in the feed. I’ll be proud to be such a pretty roast chicken. I take low doses of medication (mixed into the feed) to help get through the stress of fast growth in an unpleasant environment.

Our manure isn’t cleaned out while we live in this house. It builds up, and, once we are gone, is eventually moved to a lagoon or trucked away to local cattle or crop operations. So you can imagine that it gets pretty smelly in here.

When we are harvested, we are packed into crates on an 18-wheeler and hauled to the nearest processing facility. There, we will be mechanically eviscerated. It isn’t a perfect system, so when the cutters miss and our toxic poop goes flying everywhere, the fix is to dunk our carcasses in bleach water. Nevermind that our flesh is abnormally soft because of rapid growth, unnatural diet, and lack of exercise, causing it to absorb up to 5% of this fecal-chlorine solution. That “moisture” will make cooking our breastmeat more pleasant than it would have been had we been raised the natural way.

We appear to feed mankind at a low cost with little manpower involved using land as efficiently as possible. But the truth is that the money and manpower and land usage are spent elsewhere. Food is food, and it must be grown somewhere.

We chickens eat grain that is paid for by tax dollars, and the workers that care for us are the manure handlers and the grain growers and the businessmen that lobby for subsidies and the taxpayers that allow their incomes to pay for business decisions over which they have no control. The land we live on in such dense numbers is taken up in the corn- and soy-producing states, like Iowa and Ohio. In fact, to raise 80,000 chickens, it takes around 280 acres to grow the grain, and that’s assuming only one batch of chickens per year. Of course, to use these fancy houses efficiently, our farmers do more like 6 batches per year, making the ACTUAL average annual land usage of a poultry farm more on the order of 1,690 acres, plus the space it takes to actually have the houses and the processing facilities, etc. This is not to argue that people eat grains instead of chickens. But perhaps there is a better way to grow chickens for meat…

If I make it through the scalder, plucker, and mechanical evisceration stations at the processing unit without damage, I’ll likely be sold whole. I’ll probably end up at the supermarket with an “all natural” label on me, which doesn’t refer to the way I was raised, but rather that my carcass wasn’t injected with artificial flavors. If I have any tears in my skin, I will be parted out to be sold as leg quarters and boneless skinless breastmeat. Everyone loves eating that because it’s so easy to cook. It’s too bad they don’t try eating broth made with my bones, because that is probably the healthiest thing about me, despite my background.

Frisky Freeman, The Pasture-Raised Meat Bird

My name is Freeman, and I live on actual ground at Shady Grove Ranch. My house has about 100 other birds in it and provides us with continual access to grass, dirt, cow pies, and fresh air. We like to scratch around in search of bugs to eat. We also love eating the grass and various forbs in our pen. Tomorrow we’ll get a new patch of grass, just like we did yesterday. That’s always exciting.

We have a guardian dog nearby that scares away the predators. Our farmers, the Cadmans, come to feed us twice a day, and they sometimes take some of us out of these pens so we aren’t too crowded. When it storms, they run out in the middle of the night to prop up our pens so the water can drain. They also put hay around us to keep us warm if it’s windy and rainy.

We all grow at our own paces—at harvest time, some of us will be 5 pounds, but some of us will not make 3 pounds. We have different personalities, you know, so some of us don’t care as much about eating. When harvest time comes, we are placed into crates with enough space that we don’t get overheated. Then we are processed by hand and washed with pure water (no bleach!). We’ll be food for people who cannot eat soy or who want their chicken raised as naturally as possible. Our processors are very careful with us because they know that the Cadmans only sell to customers. If our carcasses get damaged, there is no canned-chicken or chicken-by-product company on standby to purchase rejected meat.

We are a meat breed, so we’re not into flying or frolicking constantly. But we do enjoy chasing bugs (and each other) and flapping our wings and stretching our legs. We live a great life making nutrients that only we can make. And because we get exercise and we grow without the use of antibiotics or arsenic, our flesh is firm and rosy naturally. It won’t be squishy like commercial chicken.

Every year, our farmers try new methods to figure out the best way to raise us. We have to be protected from predators, wind, and rain. Our house also needs great ventilation because it gets really hot in Texas. Our farmers want us to have fresh pasture every day, so our house can’t be too difficult to move. When we eat greens, our fat tends to have more omega-3 fatty acids, and we feel better. They also want us to be exposed to sunlight so our pupils can signal for the production of vitamin D.

We live a good life, despite the fact that we are intended for meat. We get to be chickens instead of machines, eating foods that are appropriate and living in a non-toxic environment. Best of all, we get to nourish people by the hard work we do of producing nutrients that are tasty and easy to digest.

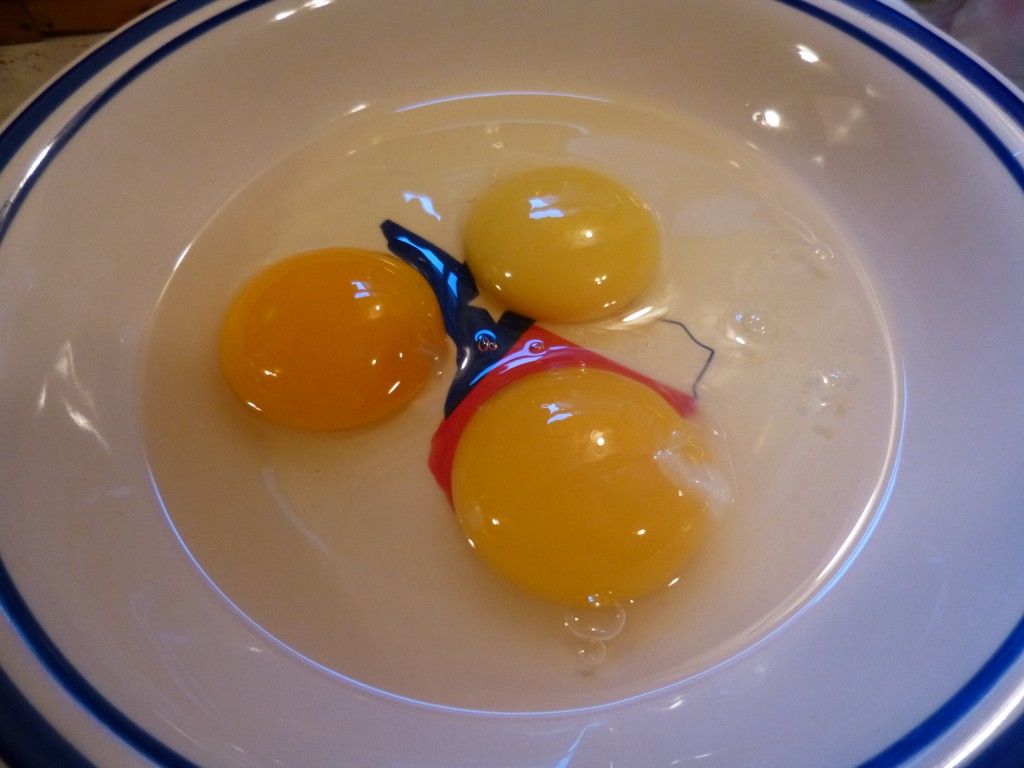

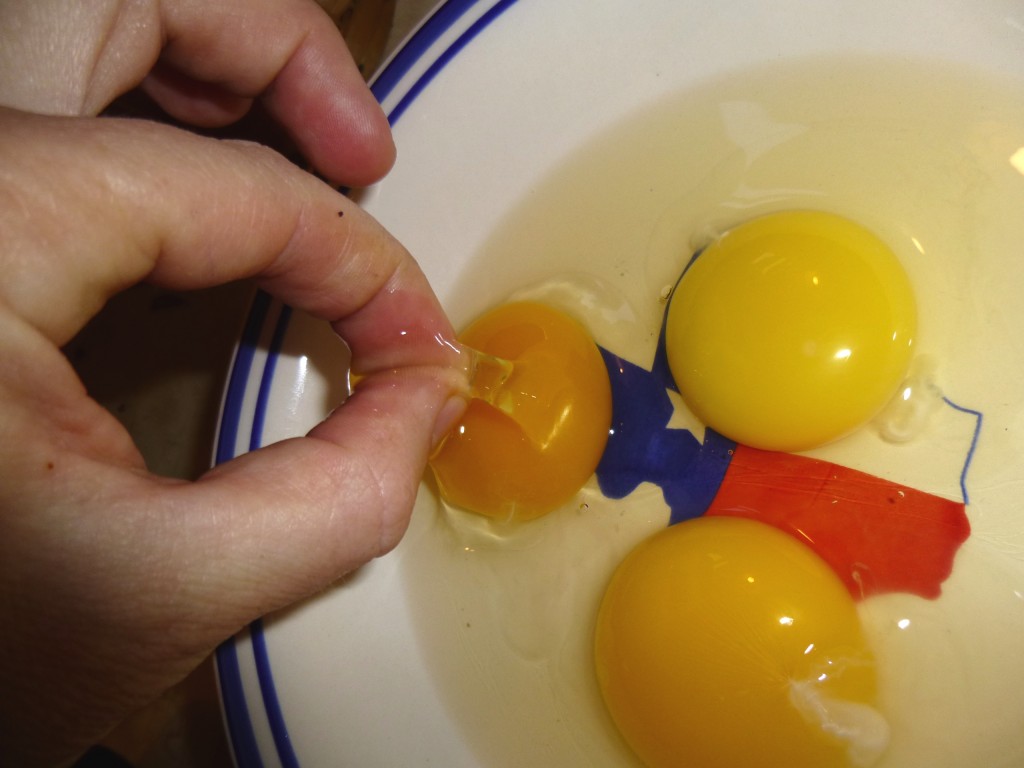

Looks good! And you can clearly see the distinction between the inner white and the outer white–which means it’s fresh! It’s so fresh that it remains intact when I grab it:

Looks good! And you can clearly see the distinction between the inner white and the outer white–which means it’s fresh! It’s so fresh that it remains intact when I grab it: